This framework develops a single geometric mechanism—a localized oscillatory singularity in spacetime—and shows that spin, relativistic kinematics, wavefunctions, superposition, measurement, and interaction structure all follow as necessary consequences of that mechanism.

The emphasis is not on reinterpretation, but on replacement of postulates by dynamics and geometry.

This page provides a conceptual map of the oscillatory spacetime framework and how its elements fit together. It is intended to orient readers to an ongoing research program, not to claim completeness or finality.

Core Insights

I. Internal Oscillation and Spin

A standard oscillatory system in three spatial dimensions is dynamically reduced to two dimensions by angular momentum conservation: any sustained oscillation lies in a plane.

The two circular modes of planar oscillation are naturally represented as a two‑component complex object, reproducing the full mathematical structure of a quantum spinor—except for its characteristic 4π rotational behavior.

The missing ingredient required for true spinorial behavior is the 4π rotational symmetry (the SU(2) double cover of SO(3)).

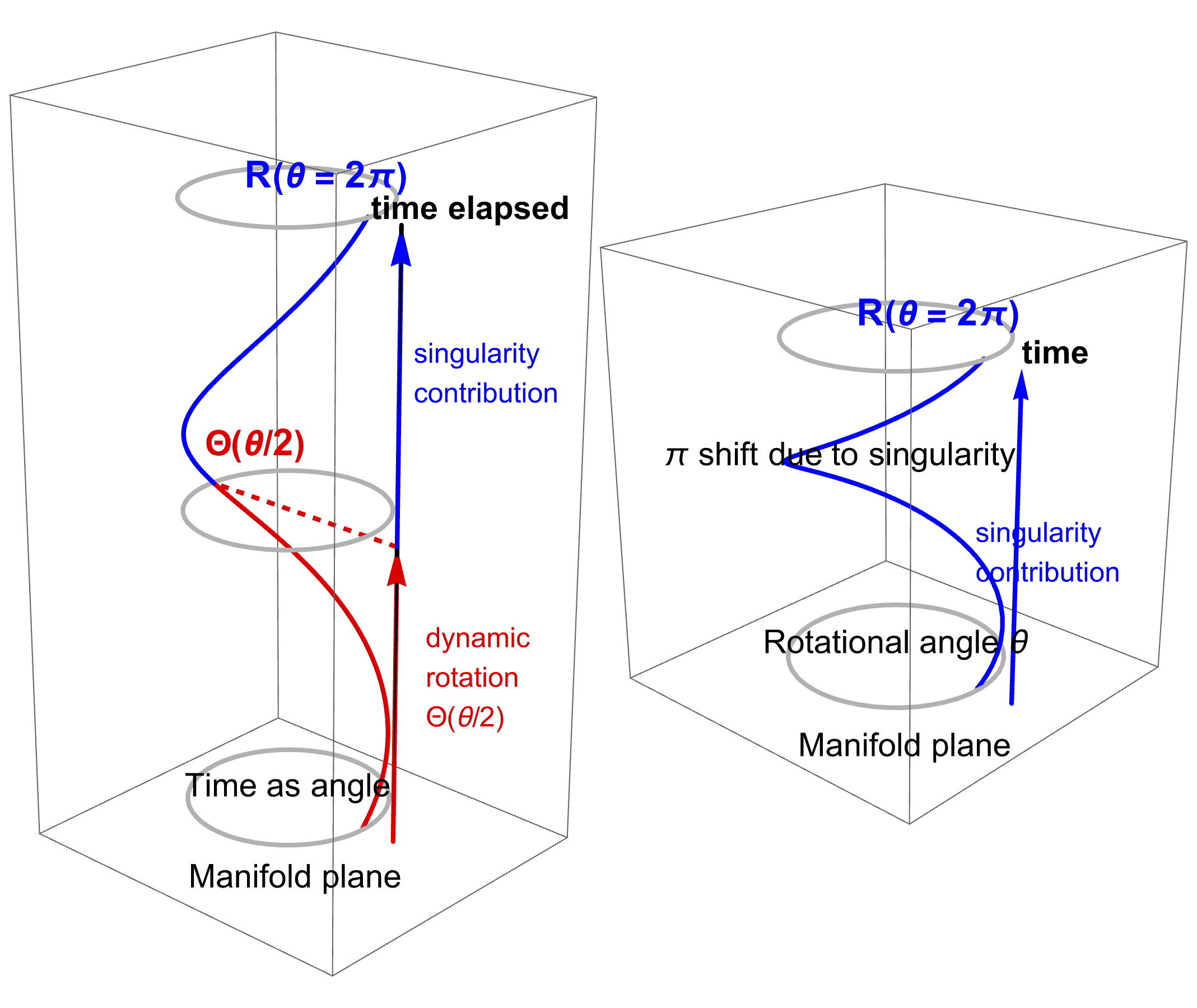

Introducing a spacetime singularity with a two‑sheeted (double‑valued) internal time provides a physical mechanism for this 4π symmetry and enforces the half‑angle transformation law.

II. Motion, Relativity, and the Helical Worldline

When the singularity translates, its internal rotation traces a helical trajectory in spacetime, rather than a straight worldline.

The helical structure geometrically couples rotational and translational motion because the excitation propagates at a fixed intrinsic (null) speed along its worldline.

Maximum translational velocity occurs when rotational motion is fully converted into translation; this limiting velocity is identified with the speed of light.

The geometry of the helix naturally produces time dilation consistent with special relativity, with the speed of light emerging as the invariant limiting speed.

The singularity is not a particle embedded in spacetime but a localized contribution to the spacetime manifold itself, carrying its own internal temporal structure.

III. Spinors, Wavefunctions, and Linearity

A stationary singularity admits a two‑component spinor description, but translational motion requires four internal modes—two spatial windings and two temporal (forward/reverse) windings—yielding a Dirac spinor structure.

In addition to the actual helical worldline, one can define a dual helix that tracks how the internal phase would be realized across alternative spacetime trajectories.

For a single trajectory, the dual helix is represented as a plane wave; linearity and superposition arise as bookkeeping properties of this representation, identifying the dual helix with the quantum wavefunction.

In the massless (null) limit, the spacetime variation of the dual helix is mathematically equivalent to the Weyl equation.

When all four internal modes are required, the spacetime variation of the dual helix is equivalent to the Dirac equation.

Helicity, chirality, energy sign (particle/antiparticle), and mass arise from a single geometric mechanism: the orientation and mixing of spatial and temporal windings of the singularity.

Many central quantum‑mechanical concepts arise from the spacetime persistence of the singularity’s internal modes, which act as a coupled clock–gyroscope mapped onto spacetime via the dual helix.

Wave–particle duality is physically resolved: the particle is a localized singularity with internal rotational dynamics, while the wavefunction is an extended representation of phase persistence.

The same spacetime geometry simultaneously accounts for both special relativity and quantum mechanics.

IV. Measurement and Interference

Measurement is understood as a localized collision between the singularity’s internal clock–gyroscope and an apparatus.

The measurement interaction induces internal dynamical changes that modify (collapse) the dual‑helix representation while transferring information to the apparatus in modes compatible with its dynamics.

Quantum interference arises when particle–apparatus interactions are temporally coherent over windows that allow multiple phase‑consistent interactions.

In the absence of such coherence, interference should not occur—providing concrete experimental opportunities to distinguish this framework from standard quantum mechanics.

V. Interactions and Particle Structure

Singularities influence the spacetime manifold through closure conditions on internal time‑phase around loops, naturally producing the radial behavior of the Coulomb interaction.

This constitutes a first step toward deriving electromagnetism from the same oscillatory‑spacetime framework.

The single‑loop clock geometry underlying the Dirac equation can be generalized to other internal geometries, corresponding to additional leptons and nucleons.

Higher‑energy charged leptons correspond to higher‑dimensional oscillatory modes that lack topological stability.

Neutrinos are identified as spacetime (rather than purely spatial) oscillations, explaining their light‑like propagation and distinct interaction properties.

A trifold knotted geometry threaded by a bound neutrino‑like rotational mode naturally produces three rotational sectors with effective charges 2/3, 2/3, and −1/3, motivating identification with quark charge structure.

Research

Bar-Yam, Y. (2025). Oscillatory Spacetime as the Physical Origin of Spinors, Wavefunctions, and Quantum Measurement. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17981536

Bar-Yam, Y. (2026). Quantum Mechanics: Experiments, Assumptions, and a Unifying Physical Framework. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.18248461, NECSI Technical Report 2026-01-01