Ashby’s law of requisite variety provides a necessary (not sufficient) condition for system efficacy: a system must possess at least as much complexity as the set of environmental behaviors that require distinct responses. The paper argues that because complexity depends on the scale (level of detail) of description, we need a multi-scale generalization of Ashby’s law.

The authors define a class of complexity profiles—complexity as a function of scale—that (1) manifests a multi-scale law of requisite variety and (2) obeys a sum rule capturing tradeoffs between smaller- and larger-scale degrees of freedom. They also extend the framework to subdivided systems and systems with a continuum of components.

Why Complexity Depends on Scale

The amount of information needed to describe a system depends on how finely it is observed. At very fine scales, complexity reflects independent variation among components. At larger scales, complexity reflects coordinated structure among groups of components.

Many systems that appear complex are not complex in the same way at all scales. A system may have high variability at small scales but very limited structure at larger scales, or vice versa. Treating complexity as a single scalar obscures these distinctions.

A scale-dependent view makes it possible to identify where complexity exists—and where it is missing.

Complexity as a Function of Scale

Complexity is represented as a profile: the amount of information required to describe the system at each scale.

Small scales correspond to fine-grained descriptions of individual components.

Larger scales correspond to coarse-grained descriptions of collective behavior.

This profile captures how information is distributed across scales rather than collapsed into a single value.

The framework applies both to systems composed of discrete components and to systems treated as continuous distributions.

The Multi-Scale Law of Requisite Variety

For a system to be effective in an environment, it must match the environment’s complexity at the scale at which distinctions matter.

This leads to a multi-scale formulation of requisite variety:

At every scale, the system’s complexity must be at least as great as the complexity of the environmental conditions that require distinct responses at that scale.

Failure at any relevant scale implies an inability to respond effectively, even if complexity is sufficient at other scales.

This formulation allows incompatibilities between systems and environments to be identified even when single-scale measures would suggest adequacy.

Tradeoffs Across Scales: The Sum Rule

Complexity at different scales is not independent.

Structure at larger scales requires constraints among smaller-scale degrees of freedom.

As a result:

Increasing large-scale complexity generally reduces independent variation at small scales.

Increasing small-scale variability limits the amount of coherent large-scale structure.

This tradeoff is captured by a sum rule that relates complexity across all scales, expressing a conservation-like relationship between fine-grained freedom and large-scale organization.

Combining and Replicating Systems

The framework supports natural operations on systems:

Independent subsystems contribute additively to complexity at each scale.

Replication of identical subsystems stretches the scale axis of the complexity profile, reflecting the increased size of the system without altering its internal structure.

These properties allow meaningful comparison between systems of different sizes and compositions.

What This Framework Makes Possible

A scale-dependent definition of complexity makes it possible to:

Identify mismatches between systems and environments at specific scales

Distinguish between disorder and structured complexity

Analyze coordination limits in multi-component systems

Reason about effectiveness without relying on arbitrary coarse-graining choices

Complexity is no longer a single quantity to be maximized, but a structured resource that must be appropriately distributed across scales.

Research

Alexander F. Siegenfeld and Yaneer Bar-Yam. “A Formal Definition of Scale-Dependent Complexity and the Multi-Scale Law of Requisite Variety”

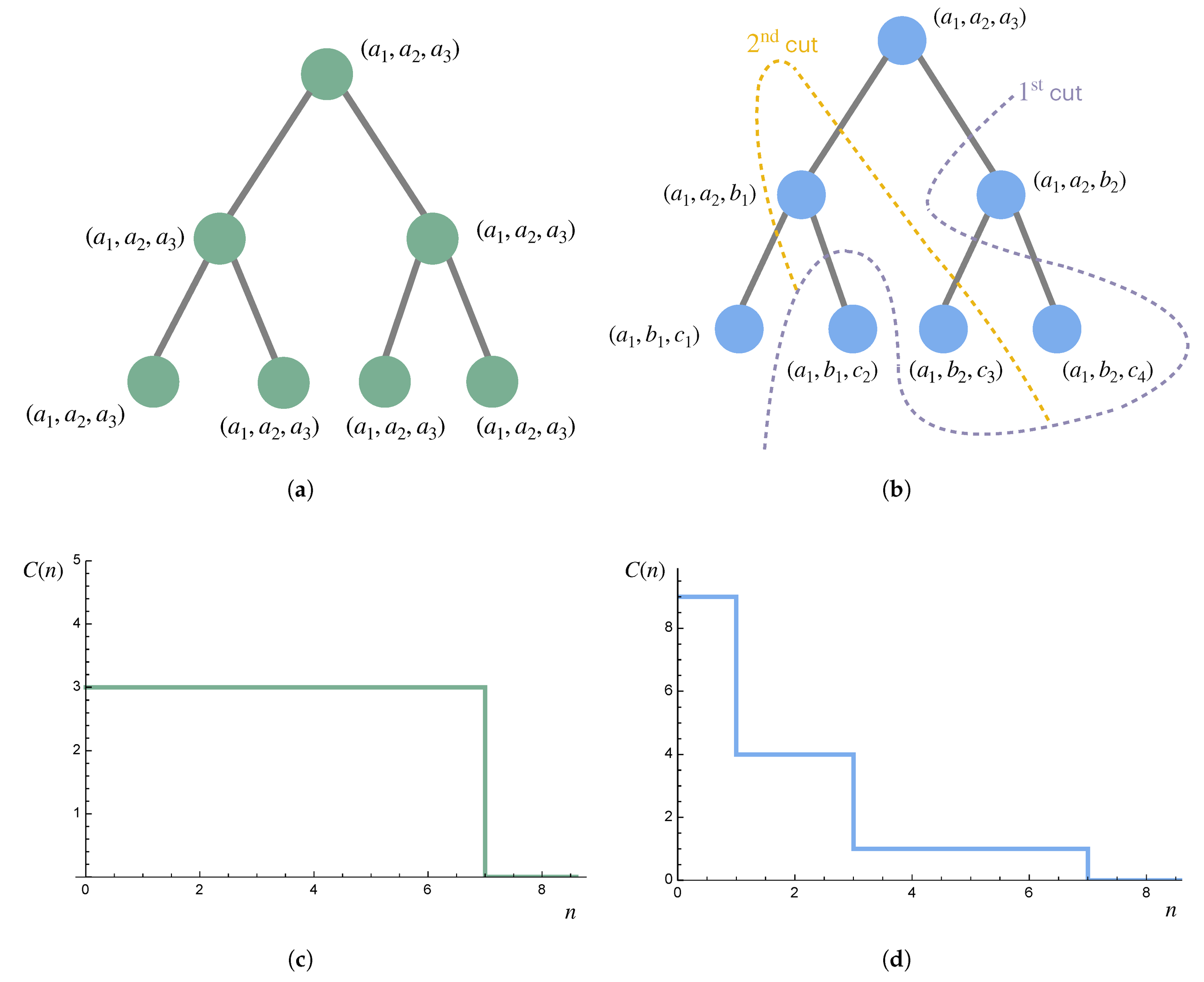

The hierarchies discussed in Example 10 are shown, together with the resulting complexity profiles (made continuous via Equation (1)) for 𝑐=1. The complexity profile in (c) can be obtained from any nested partition sequence for the hierarchy in (a). The complexity profile in (d) can be obtained from any nested partition sequence for which the first three partitions are given by the displayed cuts in the hierarchy in (b).